Why Nature Still Matters in a Hyper-Digital India

Step outside after the first monsoon rain and the world feels different. The smell of wet soil, the sudden hush in the air, the sparkle on neem leaves — nature has a way of quietly resetting us.

Nature in the Age of Screens

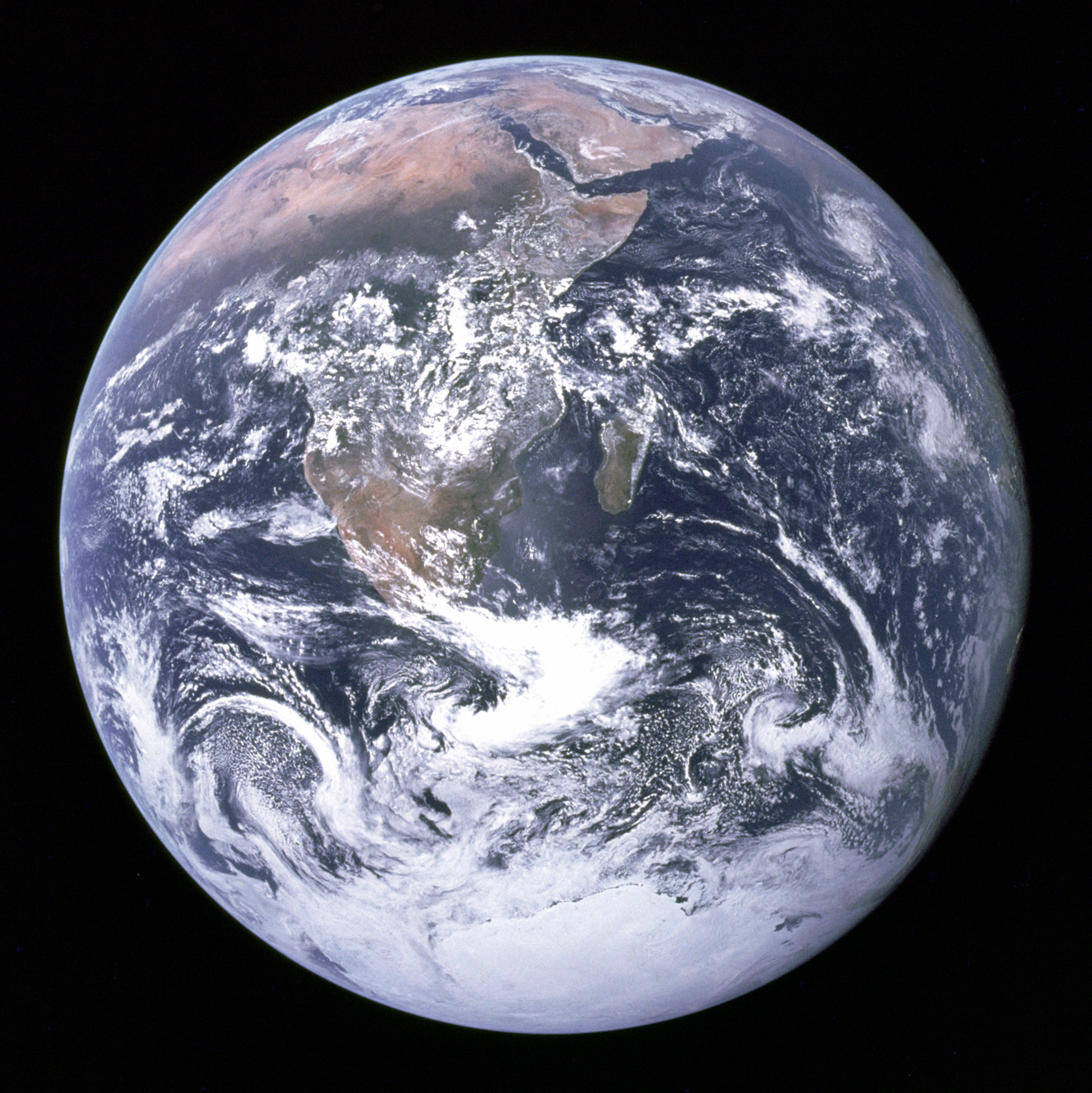

The Earth captured by Apollo 17 astronauts — a reminder of our shared and fragile home.

We live in a time where most of our waking hours are mediated by screens. Meetings happen on video calls. Groceries arrive through apps. Even friendships often unfold in chat windows. For urban India especially, daily life can pass without touching soil, climbing a tree, or watching a sunset without checking notifications.

Yet nature has not disappeared. It waits — in city parks, along the coastline, in the Aravalli hills, in the Western Ghats, and even in the stubborn peepal tree pushing through a concrete footpath.

I once met a college student in Chennai who told me he had never seen the Milky Way. Growing up under constant city lights, the night sky was always a pale orange haze. When he finally travelled to Ladakh and looked up, he said he felt both small and strangely relieved. That feeling — of perspective — is something nature gives freely.

Science backs this up. Exposure to green spaces reduces stress hormones, lowers blood pressure, and improves concentration. It is not mystical. It is measurable. Our bodies evolved in forests and grasslands, not in traffic jams.

The Science of Why Nature Heals

Biologists use the term biophilia to describe the innate human tendency to seek connections with other forms of life. The idea suggests that we are not separate from nature; we are expressions of it.

When we walk through a park, several things happen simultaneously. Our eyes track fractal patterns in leaves and branches. Our ears register layered sounds — wind, birds, distant water. Our skin senses temperature changes. These small sensory inputs calm the amygdala, the brain’s threat detector.

In Japan, the practice of “forest bathing” or shinrin-yoku has been studied for decades. Participants who spend time among trees show improved immune function and reduced anxiety. Similar studies in Indian cities have found that students who study near greenery perform better in memory tasks compared to those in concrete-heavy environments.

There is also a cognitive reset at play. Attention Restoration Theory suggests that natural environments engage what psychologists call “soft fascination.” Unlike scrolling social media, which demands sharp focus and quick reactions, nature allows the mind to wander gently. That wandering is productive. It helps us solve problems.

Think about how many ideas arrive during a walk. Not during a meeting. Not while replying to emails. But while moving through open air.

Nature and the Indian Imagination

In India, nature has never been just scenery. It is woven into culture, festivals, and daily rituals. The Ganga is not merely a river. The banyan tree is not just shade. Even the monsoon is treated almost like a character — unpredictable, dramatic, sometimes generous, sometimes unforgiving.

Farmers track the skies with a precision that rivals any weather app. Fisherfolk read tides and winds instinctively. Indigenous communities in the Northeast and the Andaman Islands maintain knowledge systems that modern science is only beginning to appreciate.

And yet, modern development often pushes nature to the margins. Wetlands are filled for real estate. Lakes shrink under construction debris. Hills are cut for highways. We celebrate GDP growth but rarely measure the loss of silent ecosystems.

This is where I hold a mild but firm opinion: economic growth that erodes natural capital is short-sighted. A city without breathable air and accessible green space may look impressive on paper, but it quietly erodes public health.

Climate Change: The Warning We Can’t Ignore

Nature is resilient, but not invincible. Rising global temperatures, melting glaciers in the Himalayas, erratic monsoons, and coastal erosion are no longer abstract headlines. They are lived realities.

In Mumbai, intense rainfall events have become more frequent. In Delhi, air quality dips to hazardous levels each winter. In Uttarakhand, flash floods have devastated towns built along fragile slopes.

Climate science is clear: human-driven greenhouse gas emissions are altering Earth’s systems. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has repeatedly warned that limiting warming requires rapid reductions in carbon emissions and significant ecosystem restoration.

But beyond global agreements, the solutions are surprisingly local. Restoring mangroves protects coastal cities from storm surges. Preserving forests safeguards biodiversity and stabilises rainfall patterns. Even urban tree-planting initiatives reduce heat island effects.

Nature is not merely a victim of climate change. It is also one of our strongest allies in adapting to it.

Relearning Our Relationship with the Natural World

For many of us, reconnecting with nature does not require dramatic lifestyle changes. It can begin small.

- Walking to a nearby park instead of scrolling during breaks.

- Growing tulsi, mint, or chillies on a balcony.

- Choosing public transport or cycling when possible.

- Supporting local conservation efforts and eco-conscious businesses.

Schools can incorporate outdoor learning. Offices can design greener campuses. Urban planners can protect wetlands rather than treating them as empty land.

There is also something deeply democratic about nature. Access to a clean riverbank or a safe public garden should not be a luxury. It should be basic infrastructure.

During the pandemic lockdowns, many Indians reported noticing birdsong more clearly than ever before. With traffic reduced, skies looked bluer. It was a glimpse — brief but powerful — of how quickly ecosystems respond when human pressure eases.

That memory should not fade.

Why Nature Still Grounds Us

At its core, nature offers perspective. The Earth has existed for 4.5 billion years. Civilisations rise and fall in what is, geologically speaking, a blink. When we stand before the ocean or beneath a star-filled sky, our anxieties shrink to human scale.

This does not mean nature solves all problems. It does not replace policy, innovation, or economic reform. But it reminds us of proportion.

In a country racing towards digital transformation, artificial intelligence, and space missions, we must remember that progress and preservation are not opposites. ISRO launches satellites into orbit, yet its launch sites sit amid coastal ecosystems that must be protected.

Nature is not an escape from modernity. It is the foundation that makes modern life possible — from the water we drink to the climate stability that allows agriculture to thrive.

Perhaps the simplest way to understand this is through a quiet moment. Stand barefoot on soil after rain. Notice the scent, known scientifically as petrichor. That smell comes from compounds released by soil-dwelling bacteria. Even in that small sensory experience, biology, chemistry, and memory converge.

We are not observers of Earth. We are participants.

As India urbanises and innovates, the real test of maturity will be whether we can grow without severing our roots. Protecting nature is not nostalgia. It is long-term intelligence.

And sometimes, all it takes to remember that is a walk outside.

Comments